Exclusive Data: Freshmen, Held Back During Pandemic, Fuel ‘Bulge’ in 9th Grade Enrollment

By Linda Jacobson | May 9, 2022

Learn4Life, a national charter school network, typically serves older teens who are struggling to make up enough credits to graduate. But when a new site opened in San Antonio this school year, Principal Crissy Franco got an unusual number of registration requests from 14- and 15-year-olds.

They included ninth graders who didn’t earn any credits in their first semester and those who should have been in 10th grade, but were out of school for a year.

“You don’t normally refer younger kids to dropout recovery,” Franco said. “Some of them are like, ‘What’s a credit?’”

Those students who were held back are among the reasons Texas saw a 9% increase in its freshman class this year, more than four times the state’s annual growth rate prior to the pandemic.

That pattern has been demonstrated in more than a dozen states, according to enrollment data compiled by Burbio, an information services company, and shared exclusively with The 74.

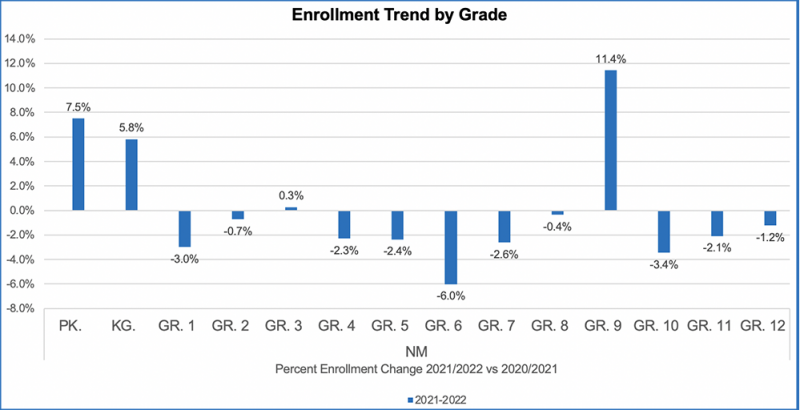

The new data, from 35 states and the District of Columbia, adds to the complicated picture of students’ comings and goings during the COVID era. With many young children who delayed pre-K and kindergarten during school closures now flooding back into the education system, an enrollment surge in the early grades was expected. But 15 states and D.C. saw growth in ninth grade of at least 5% compared to 2020-21, and in a few states, including New Mexico and North Carolina, the increase in freshmen far outpaced that of kindergartners.

While the return of families to public schools contributed to growth in ninth grade this year, retention rates have nearly doubled in some states and districts, and educators don’t expect next year to be much better.

“We’re a generation that’s going to have people with two-year holes in their education,” said Jeffrey Cole, principal at Winston County High, a rural Alabama school about midway between Huntsville and Birmingham.

If freshmen only fail two quarters, Cole usually moves them on to 10th grade. But for the first time in his 19 years as principal, he has students failing all four quarters. He thinks they should have stayed in eighth grade. Across the state, enrollment in ninth grade has jumped at a much higher rate than before the pandemic.

Districts often see a “bulge” in freshman year when students don’t pass enough classes to move on, said Eric Wearne, director of the Education Economics Center at Kennesaw State University, outside Atlanta. But he added it’s not a surprise COVID disruptions and remote learning made matters much worse.

“Students were in ninth grade,” he said, “and the COVID situation was so tough that more of them than usual didn’t earn enough credits to be considered 10th graders yet.”

Retention data in some states and districts back that up. Figures from last fall show that 18% of ninth graders in the Houston Independent School District repeated the year, significantly higher than the district’s pre-pandemic rate of 10%. And in North Carolina, more than 16% of last year’s freshman class was retained — roughly double the rate of past years. District officials from rural Maryland to Albuquerque, New Mexico, also saw higher retention rates this year.

The majority of states where ninth grade enrollment surpassed 5% are concentrated in the South, where they have “well-defined promotion criteria” for freshmen, such as end-of-course exams, explained Robert Balfanz, who directs the Everyone Graduates Center at Johns Hopkins University. Such policies were widely implemented in the early 2000s at the start of the accountability-driven No Child Left Behind era, but have since been suspended in many states.

What hasn’t changed, he said, is that students still need to earn enough credits to graduate.

“It’s the long tail of the pandemic,” he said. “This will impact graduation rates three years from now.”

He added that during remote learning, high school students were more likely to have assignments without live instruction and had to “self-manage getting the work done.” With many high schools canceling orientation in the fall of 2020, he said rising ninth graders might not have fully understood the consequences of failing a class.

‘Fell off the radar’

The retention increase is one example of how the pandemic has altered existing patterns that enrollment forecasters use to help districts plan for the future. In his work with school districts, Jerry Oelerich, a senior analyst at the consulting company Flo-Analytics, accounts for the fact that 2007 — when most of this year’s ninth graders were born — was a record-setting year for births. That alone, however, doesn’t fully explain the big increases some states are seeing in ninth grade, Oelerich said.

Private school enrollment and homeschooling also grew last year. But students often return to traditional high schools to play sports. And many parents decide they’re not cut out to teach high schoolers.

“Their expertise kind of runs out,” said Kent Martin, a senior analyst at Flo-Analytics and a former teacher and administrator in Washington state. “You really need to be a content expert, like a teacher.”

Ronn Nozoe, CEO at the National Association of Secondary School Principals, said it makes sense that with schools predominantly open this year, families who opted for private schools would return and “save their money.”

“There are a lot of kids who fell off the radar,” Nozoe said. “If you’re going to move back in, you want to start that in ninth — not 10th, 11th or 12th.”

That’s what Virginia mother Kate O’Harra decided after she pulled her son Jack Mulhall out of the Loudoun County district last year and enrolled him in Stride (formerly K12), a national network of virtual schools, for eighth grade.

“He didn’t do terrible,” even though O’Harra, a pilates instructor, and her husband, an IT professional, weren’t always available to help him with schoolwork. When schools closed, Jack was on his way to overcoming some of the scatteredness that comes with his ADHD. But the district’s remote learning program, which O’Harra described as “a complete and utter failure,” interrupted that progress.

“We were in a good place pre-COVID. Now it’s all over the map.”

The affluent suburb has been at the center of several highly politicized controversies over the rights of transgender students and the use of so-called “critical race theory.” But Jack’s desire to return to school with his friends and her wish for a normal school structure convinced O’Harra to return to the district for ninth grade.

Still, the move hasn’t solved everything for Jack, now at Woodgrove High School.

“We went into 9th grade very unprepared,” said his mother, adding that after a year of remote learning, he struggles with some social cues, like not knowing how to take a joke.

Jack said his only contact with friends during eighth grade was playing “Call of Duty,” and the one person he met virtually through Stride was his math teacher. He’s still missing some organizational skills and fell behind in Spanish and earth science. He’ll start next year with a tutor.

“I didn’t really have assignments for science [in eighth grade]. I was left drifting without any knowledge,” he said. But back in a traditional school, Jack plays football and lacrosse and said, “I can actually see and talk to my teachers in real life.”

Nationwide enrollment in Stride dropped slightly this year — down to 187,000 from 189,400 last year, but still well above the pre-pandemic figure of about 123,000.

Virtual programs are another reason some district’s ninth grade classes are swelling. The Mecklenburg County Public Schools in Virginia, a rural district not far from the North Carolina state line, offered a virtual option through Stride so parents still concerned about COVID wouldn’t withdraw their children to homeschool and the district wouldn’t lose funding.

The virtual program boosted ninth grade enrollment from 337 in 2020-21 to 609 this year. But Superintendent Paul Nichols has regrets and suggested that remote instruction shares some of the blame for students veering off track.

“We will offer no virtual education options for students next year,” he said. “We are concerned that most of them have not completed much, if any, actual academic work.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter